What the eye does

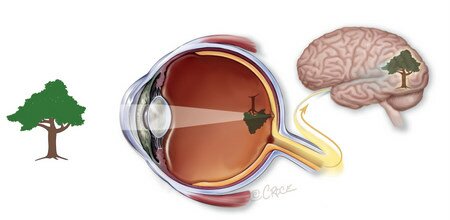

The human eye captures information that is only perceived once processed by the brain.

The eye receives information via reflected light – it can only make sense of what is in a room if there is some light to illuminate its contents. If it is pitch black, there is nothing for the eye to work with.

Reflected light enters the eye and is focussed on its rear internal surface, known as the retina. Light receptors located on this surface process the light into electrical signals and transmit these signals to the brain along the optic nerve.

When the brain receives this electrical information from the optic nerve, it interprets it as an image.

How the eye does it

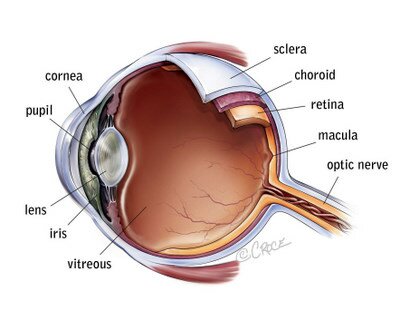

Light enters the eye through the cornea, the clear bulge at the front of the eyeball. The cornea gathers the light into the pupil, a hole in the centre of the iris, which is the structure that gives the eye its colour.

Depending on the amount of light available to the eye, the iris will contract or expand to accommodate the amount of light required, making the pupil smaller or larger. The more light that is available, the smaller the pupil becomes; restricting the amount of light entering the eye. The less light available, the larger the pupil becomes; allowing more light to enter the eye.

Once the light passes through the pupil it goes through the crystalline lens, which sits behind the iris. Light then passes through the vitreous humour, the clear gel that fills the inside of the eye. Finally, light comes to focus on the retina.

The retina is a filmy tissue made up of a number of layers of different types of cells. One layer of the retina contains light receptors known as rods and cones. These light receptors allow the retina to convert light into electrical impulses, which are then transmitted along the optic nerve to the brain and decoded into vision.

The macula sits at the centre of the retina and processes fine detail into accurate vision. The fovea, inside the macula, processes even finer detail.

Measuring vision

Visual acuity is the measure of how well someone sees. This can be determined by testing how clearly they can see text at a standard distance. This is done with a Snellen chart, named after its inventor, Herman Snellen, a Dutch ophthalmologist who worked at the turn of the 19th century.

The Snellen Chart

The Snellan chart typically features eleven rows of letters, which are largest on the top row (which usually has one letter only) and smallest on the final row (which usually has nine letters). Each row indicates a specific level of acuity; one row represents what is accepted to be normal vision, a visual acuity of 20/20.